The Aches and Pains of Working From Home During COVID-19

Are stress and uncertainty weighing you down?

Working at a major medical center in NYC during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, it came as no surprise that we encountered a number of patients seeking care from both of us: a clinical psychologist specializing in pain and a physical therapist treating spinal disorders. The social disconnectedness, emotional distress, ambiguous loss, and physical suffering that resulted from the stress of an unknown disease and lockdown highlighted the need for both psychological and physical attention.

Moretti and colleagues found that working at home during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in an increased risk for mental health and musculoskeletal problems, particularly those affecting the spine (Moretti, Menna et al. 2020). Ongoing stress, sleep disturbance, fatigue, back pain, and headaches were magnified in many of our patients triggered by the altered work demands and increased uncertainty that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Commonwealth Fund’s Charity Versus Arthritis initiative conducted a survey of employees working from home as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Webber 2020). Researchers in that study found that 50% of respondents had low back pain and 36% had neck pain, while 46% of respondents reported that they had been taking painkillers more often than they would like (Webber 2020). In the same survey, 89% of those suffering with back, shoulder, or neck pain as a result of their new workspace had not told their employer about it. We saw the effects of this cumulative stress and silent suffering in individuals who broke down physically and emotionally.

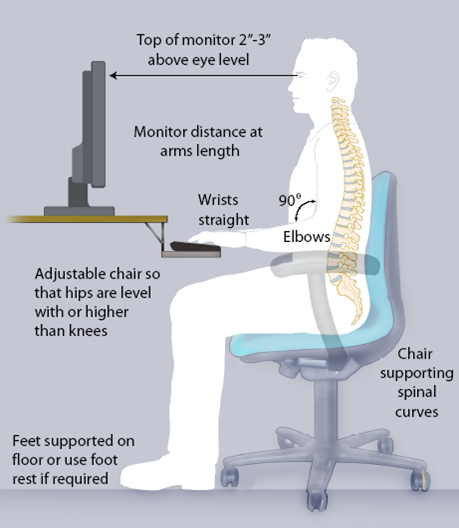

Source: Johnson & Sonty, 2021

We present two composite cases below that contain features of common patient presentations in order to illuminate the interaction of the psychological and physical anguish experienced by our patients during the COVID-19 lockdown. In one instance, we treated a patient who had to manage the virtual classroom and other daily needs of her children while struggling to maintain a professional demeanor in a demanding job with ongoing Zoom meetings. She shared that she felt that she was failing as a parent and in keeping up with her work responsibilities. Her premorbid anxiety worsened and her health suffered as her weight increased. She sat for long hours slouched in front of multiple screens with rounded shoulders and a forward head posture.

There is evidence that people who increase time working on a computer, or looking at a mobile device, suffer from poorer health decisions and outcomes (Vizcaino, Buman et al. 2020). Even before the COVID-19 pandemic forced many of us to increase our screen time, research indicated that most adults spend as much or more time looking at a screen as they do sleeping (Hammond 2013).

The rounded shoulders with forward head posture is a protective posture that harkens back to pre-civilization when protecting one’s throat was an appropriate response to stressors posed by predators. Activation of the fight or flight syndrome led our ancestors to undergo short-lived physiological changes in the form of rapid shallow breathing, increased heart rate, and a heightened ready state of the musculoskeletal system. In developed societies where stress and anxiety are often the result of sustained, less identifiable threats, our responses become maladaptive and may perpetuate pain syndromes with altered breathing patterns and excessive muscle tension in the back, neck, and shoulders.

Source: Johnson & Sonty, 2021

In the case of this individual, her pre-pandemic symptoms of neck pain, headaches, and jaw pain all worsened and compounded her emotional distress, motivating her to seek help. We encountered some variation of this response across a wide swath of individuals when confronted by the novelty of the pandemic and the changes that it forced upon their lives.

Triggered by some combination of increased screen time, ill-defined work hours, social isolation, and family pressures, patients reported feeling that their physical condition deteriorated, as their ailment progressed to a state that threatened their emotional well-being and livelihood. One less reported example of unforeseen social changes with family pressures occurred with the reuniting of parents with adult children who returned to the safety of the family home when the lockdown was enforced.

We shared a young adult patient who left his apartment to move in with his parents. He urgently sought telehealth sessions during the pandemic as a result of what was rapidly becoming incapacitating back, neck, and shoulder pain that was not being controlled by increased pain and anti-inflammatory medications prescribed by his physician.

The family dynamics contributing to his condition were regularly on display during telehealth physical therapy sessions, as he insisted that his mother fulfill the role of videographer (most patients are successful at managing the camera independently during virtual physical therapy sessions), and then reprimanded his mother for her awkward handling of the mobile device. As their interactions became more frequent, tension rose in his upper trapezius muscles, his shoulders ascended towards his ears, and his headaches, back and neck pain mounted. In order to effectively treat his complaints of back, neck, and shoulder girdle pain he had to address both his ergonomic setup at his parent’s house and his feelings around being at home with his mother and father.

We prescribed exercises to stretch his pectoral muscles in the front of his chest, retract his chin to optimize spinal alignment, and practice diaphragmatic breathing as he performed a body scan and released unwanted muscle tension. He improved measurably with the care he received, but his greatest relief came when he moved back to his apartment and a more independent lifestyle. Interestingly, his mother sought in-person care for similar conditions to her son as soon as the lockdown restrictions were loosened.

When we accept stress as a change in our ongoing pattern of life that forces us to adapt, we can readily recognize that we have all dealt with a major stressor in 2020 and will likely continue to encounter stressors in 2021. If we respond with resilience when confronted with adversity we can cope with stress-induced anxiety and musculoskeletal pain. Coping well can be done in small bites. Here are some tips: